Filled with common sense but devoid of rationality

Dear Tom,

I keep lots of little notes on my phone that I fill with thoughts about various topics. Once a note is full enough, it goes into the queue of letters to be written. I began the note I’m using now during my holiday in Budapest, and I've slowly added to it in the subsequent months. I created the note because I was unusually struck by the redundant and superfluous aspects of the city, created long ago by the Hungarians who lived there once upon a time. I’m talking about the spiky towers and bulging domes that litter the skyline, the uncountable number of churches, the overflowing fountains topped by regal statues, and all the rest; those redundant and superfluous aspects that make Budapest worth visiting. Every great European city has its own redundancy and superfluity, but for some reason I was particularly aware of it in Budapest.

I also became aware that this superfluity provokes in us conflicting emotions. We regard it with both awe and skepticism, respect and mocking; we’re at once admirers and cynics. Building the city’s umpteenth church strikes us as a ridiculous idea, and yet we’re thrilled that we can visit them all. We find the idea of statues of famous ancestors and contemporaries laughable—I googled “Obama statue” and the results are pretty weird—even though erecting statues is such an obvious and natural thing to do. Indeed, everything about the old city centres of Europe strikes me as exceedingly natural. You instantly feel at home in them. And we would still build cities like that if they weren’t also exceedingly irrational (and ifyou don't think they're irrational, just try and explain the street map of Venice). I think it's this that produces these conflicting emotions: we value rationality, and rationality is incompatible with redundancy and superfluity.

I find this tension fascinating, and in my little note I listed some objects and activities that are both perfectly natural and entirely irrational; those things we regard with skepticism and envy and admiration and disdain. Here’s what I jotted down.

The first item on my list is “lighting candles”. Interestingly enough, candles still represent something significant to us. They’re laid out in churches, for example, to be lit by anyone who wants to. Notably, there’s no explanation as to why you’d want to light a candle. It doesn't need an explanation. However, if we’re honest, lighting a candle in a church is a bit ridiculous. Eating a candle-lit dinner at home is a bit ridiculous too: you spend 20 minutes looking for the matches and the rest of the evening trying to guess what you’ve put on your dimly lit fork. But it tugs on our romantic sides nonetheless.

My dad, an agnostic at best, has lit a candle in almost every church we’ve visited together since my move to Europe, entirely undeterred by the 2 euro surcharge. He looks satisfied and perhaps a little awkward as he does it, perfectly capturing our contradictory relationship with candle-lighting. I’ve never asked him why he does it, but I don’t exactly need to: it’s a perfectly natural thing to do. To light a candle is to add your own little light to everyone else’s; to play a small role keeping darkness at bay, if only for a moment. Perhaps he also thinks of his brother and his parents, and shares a moment with them too. Lighting candles is, in short, a ridiculous and profound thing to do.

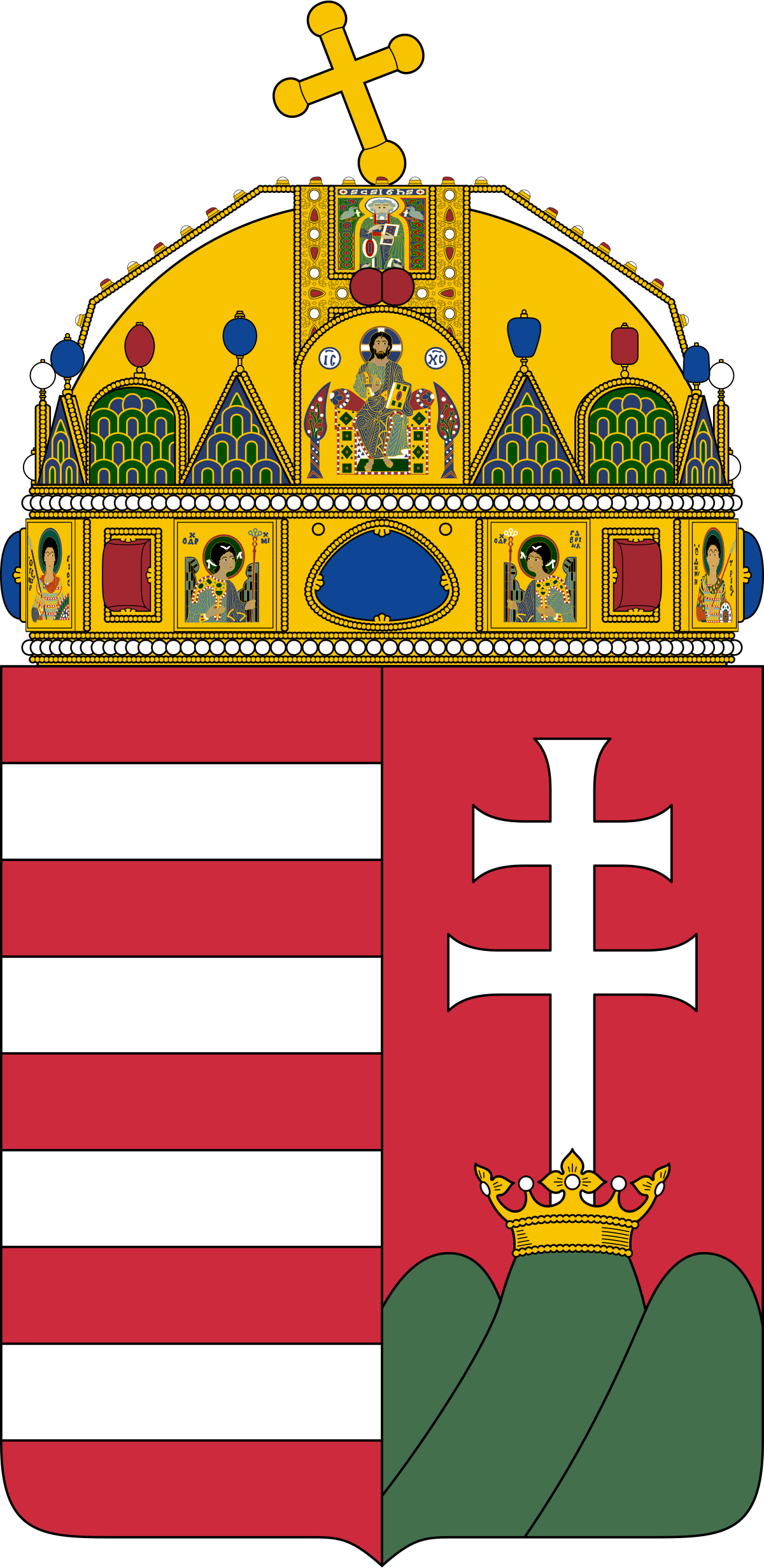

Moving on, I was inexplicably thrilled by the number of crests and emblems that were scattered throughout Budapest. The Hungarian coat of arms was proudly displayed everywhere, either as a whole or in parts (with some parts dating back nearly a millennia!). Whether for a country, a city or a family, heraldic symbols make sense; they’re an acknowledgment of the very real boundaries that exist between each of them. A coat of arms or a family crest represents a history and often a set of values: books, lions, crosses, trees, swords and shields all say something about their bearers and how they choose to distinguish themselves from everyone else.

As a child, I obsessively drew and redrew a potential family crest. It consisted of family members’ favourite colours and a couple of our favourite animals. There was a great big shield in the middle, of course (which represented my dad and was coloured blue in his honour) flanked by two kudu (my mum’s favourite animal). In my childish wisdom, a family crest struck me as perfectly sensible, which to me is a testament to how natural a phenomenon they are. Now we can only laugh at such efforts—who apart from the royal family would be pretentious enough to wear a family crest today? (Don’t worry, we’ll get back to the royal family.)

Statues and monuments fall into a similar category to that of heraldic symbols: they’re a nod to history and the shaping of a nation. I’ve already mentioned how natural a phenomenon statues are, yet, students of resentment studies aside, even those of us with a brain cell left struggle with the idea of erecting monumental statues. Clearly some people are more important than others, but—and let me know if you disagree—we seem uncomfortable with admitting that. Should they really be immortalised in stone or bronze?

But even if we got our heads around that, our ability to make great monuments is further hamstrung by our attitude towards symbolism. Among the best monuments we inherit are those of great men or gods flanked by angels, animals and various symbolic objects. Rome is full of them. In addition to our reluctance to celebrate great people, symbolism is something we struggle with too. It seems rather silly; a bit over the top, let’s say. It’s certainly not rational—we don’t even believe in angels any more. We’re too self-conscious to attempt such things now, our appreciation of the monuments of old notwithstanding.

Perhaps even more ridiculous than statues, however, are relics. Back in Budapest, in St Stephen’s Basilica, we came across the Holy Right Hand, which is purported to be St Stephen’s very own right hand. It was shrivelled and biltong-y, and encased in the most stupendous decorations. It was surrounded by a mini-cathedral of gold and silver, laid on a heavily embroidered handkerchief, itself laid on a velvet pillow. Occasionally, Hungarians would cross themselves in front of the relic, which is said to have protective powers. The preservation of body parts might be a bit…much…but the preservation of relics and their association with something mystical also strikes me as natural. How quickly does the jewellery of someone dear who’s died get imbued with magic? We might deny it—a ring is the same bit of gold it was before its owner died—but it’s certainly not how we act. Despite ourselves, we spontaneously mirror the church’s tendency to revere objects associated with people important to us.

The next things on my list are uniforms and decorative outfits, as well as badges and medals of various kinds. I’m a fan of school uniforms, but they can be hard to justify—especially when you start dolling out punishments for missing garters or forgotten blazers (I’m not resentful at all…). Even harder to justify, however, are the elaborate outfits of noteworthy figures such as the king, the pope, judges, military leaders, etc. It’s not surprising that “priests” in America rock up in jeans and a t-shirt; it would be ridiculous to wear anything else. Equally ridiculous are the uniformed chests of lieutenants and sergeants, heavily decorated with badge after badge. As our attitude toward statues reveals, we’re suspicious of elevating some people above others.

Despite the quite rational pushback against these adornments, I think they’re still important. Whatever we want to believe, these people aren’t just ordinary people. The king is the king, he should wear a crown—what could be more natural than that? The priest is our shepherd, and he should distinguish himself accordingly. And, if Jocko Willink is to be believed, the sergeant is a seriously powerful dude. He should be decorated with honours fitting of his achievements and abilities.

Finally, there are grand ceremonies such as coronations and royal weddings. These are rituals of common sense, even if they’re entirely devoid of rationality (it’s best not to think about the cost of these ceremonies for too long). As far as I'm concerned, the new king should undoubtedly be crowned with an enormous ceremony. He should stand in the abbey where generations of monarchs have stood before and receive his crown. And if you have to drag the Stone of Scone from Edinburgh for the occasion, so be it: leave no stone unturned! We decided earlier that the king isn’t just an ordinary person—nor are his sons and their brides to be—and all the stops should be pulled when something noteworthy happens to them. It isn’t rational, but it makes all the sense in the world.

I’ve pretty much said the same thing six times, but this was on my mind as we wandered through Budapest. Of course, to say something is natural does not imply that it’s good. But there seems to be something good about everything I’ve mentioned. It at least feels like we’ll lose something if we succumb to the nihilistic force that seeks to tear it all down. The question “what’s the point?” only does us a disservice; it freezes us in place and strips us quite literally of all our decorations. With rationality on its side, nihilism is tricky to overcome. Perhaps we should confiscate some (though of course not all) of rationality’s power over us and rely a little more on common sense instead.

I’ll end with a Roger Scruton quote that I’ve shared before. It really struck me when I read it, and I think it’s applicable here:

“But it is part of the conservative spirit of the English not to look too closely at inherited things – to stand back from them, like Matthew Arnold, in the hope that they can go on without you. Their institutions, the English believe, are best observed from a distance and through an autumnal haze. Like Parliament, the monarchy and the common law; like the old universities, the Inns of Court and the county regiments, the Anglican Church stands in the background of national life, following inscrutable procedures, and with no explanation other than its own existence. It is there because it is there. Examine it too closely and its credentials dissolve.”

A chaotic letter if ever there was one. Thank you for indulging me, Tom. I hope you have a wonderful festive season, and spend a special time with your family and whoever else you happen to be with. It’s been a great 2023. Here’s to a great 2024.

James